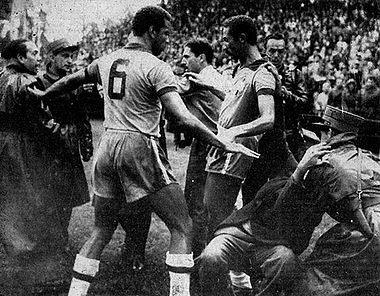

Every World Cup should have at least one Donnybrook, if you ask me. In 1954 it was Brazil v Hungary. The referee that day was Englishman Arthur Ellis, already a legend in his own head. Gordon Thomson in his book The Man in Black looks at the ref who blazed a trail for self-important egomaniacs everywhere to start writing autobiographies.

The Man of Every Match leads out the teams at the Bernabeu

By 1954 the referee was beginning to become as famous as the game itself, at least in his own mind. Arthur Ellis proved the dictum that a book should never be judged by its cover, unless it’s about art history, of course. The handful of out of print referee biographies that lie gathering dust, but mercifully not value, in London bookshops, paint an idyllic picture of the British referee in post-war international football, which is at once factual and gravely misleading. To suggest that by 1950 the referee was becoming a popular source of post-match conversation is certainly beyond doubt. Newspaper reports of matches and contemporary radio programmes confirm the growing interest in the behaviour of the man in black. But to imply that he was responsible for the spectacle of the match in the first place – which perhaps unwittingly is nevertheless what referee biographies often do – is stretching it a bit.

Ellis more or less started the trend for referee books in 1962. An avuncular man, he was nevertheless so consumed by his own worth that he compiled a football weltanschauung – The Final Whistle – as a bookend to his glorious international career. Ellis is best known for his part in the ‘Battle of Berne’, the infamous 1954 World Cup Quarter-Final between Brazil and Hungary.

In the course of the game Ellis controversially dismissed three players resulting in mini-riots in the tunnel and in the Hungarian dressing-room after the final whistle. The scene culminated in the podgy Hungarian hero Ferenc Puskas (who was injured and hadn’t even played in the game) bottling the Brazilian centre-half, Anheiro, with a glass soda siphon. Ah, the good old days.

Ellis, you may recall, ended his ‘glorious career’ on another field of play, as Stuart Hall’s prancing sidekick on It’s a Knockout. It was Ellis, indeed, who coined the phrase ‘They’re playing their joker’.

But The Final Whistle – ‘as told to Steve Richards’ – is no joke; it’s pure unashamed hagiography. On the cover Ellis, resplendent in stiff, starched white collars – half Errol Flynn, half Frankie Howerd – stands on the centre-spot smiling a knowing smile. The sun lights his large face and all around him two national captains and a balding linesman follow the flight of a flipped coin. Here, clearly, is a significant figure.

His book confirms this. “The most famous international referee of all time has retired after thirty years with the whistle,” the sleeve notes gravely intone. “His career abounds in excitement, drama and danger,” they continue, “His full and exciting life makes a remarkable story… this book recaptures all the thrills.”

This, we are by now beginning to suspect, is an important book. And one festooned with insert pictures confirming the international repute of its protagonist: Ellis enjoying fun and games with a bushy-haired Bruce Forsyth; Ellis receiving a bunch of flowers from the captain of the Russian national team in 1954; Ellis chatting pitch-side to a young German man in a wheelchair; Ellis posing with a Central-American beauty queen; Ellis relaxing on Argentinian President Juan Peron’s yacht. In one picture the phantom-like Ellis appears on the shoulder of the king of Sweden as the monarch meets the German national team, his beaming face eerily recalling one of Stalin’s more bizarre revisionist exercises. Woody Allen’s Zelig and its pale imitator Forrest Gump were still decades away.

Britain’s post-war referees saw in the game’s rapidly expanding boundaries the opportunity to become stars in their own right – and they seized it with gusto. With financial rewards scant and regular televised football still a distant dream, the referee to the world stage in his quest for recognition. The referee became a personality, although he was seldom treated with the gravitas he felt his position merited.

Ellis was undeniably an extremely capable referee, who officiated in three consecutive World Cup finals between 1950 and 1958. He claims, however that the “wonderful” experience of being involved was continually dampened by FIFA’s blatant disregard for the referee in general, and his wallet in particular. “Financially the tournaments were a dead loss for the referee,” he says. “I’ll give you the figures. The daily allowance was £4 18s plus hotel and travelling expenses – it should have been £10 – and we were not paid a penny for handling a match, even if it was the final of the World Cup.” It nearly prompted Ellis to take drastic action: “If, like some of the referees, I had had wages stopped for time off back home… I might have been compelled to send my wife back out to work.” This was the 1950s.

Bitterness at not being given enough respect is clearly Ellis’s abiding memory of the World Cup. “The referee, who becomes the prominent figure of the match if he makes a vital… decision, is just an insignificant minnow, it seems, when FIFA get down to sharing the spoils. In the showpiece of world soccer, staged only every four years, he is surely entitled to a reasonable financial return for his services, even if he isn’t there to entertain.”

But entertain he did. If recognition was what Ellis craved then he certainly got a bundle of it in 1954 following his part in the ‘Battle of Berne’ fiasco. Mostly, it must be said, from Brazilians threatening to have him shot. In fact, the Brazilian team were largely to blame for the whole incident.

They took the field that day in a state of collective hysteria. Geraldo Jorge de Almeida, the best known commentator at the time, visited the team in their dressing-room before kick-off to call upon them to avenge the deaths of the many Brazilians killed in Italy during the war. Quite what this had to do with Hungary wasn’t clear.

The head of the Brazilian delegation then launched into a protracted speech about patriotism and miracles. Suffice to say the team – and its entourage – were being deliberately and successfully cranked up for action: they knew they were about to face the best team in the world. That the game was actually completed at all was down to Ellis. Although he sent off three players and was later accused of favouring the mighty Magyars, his severe actions were certainly warranted. One of several neutral commentators to praise him after the final whistle was an Italian who described his performance as “magisterial”, adding that Ellis’s slightly dictatorial refereeing had been “necessary and legitimate”.

The Brazilians, of course, fabricated a conspiracy theory to suit their needs. One of the country’s leading referees, Mario Vianna, approached Ellis at the end of the battle wielding a huge microphone he had snatched from a reporter and accused Ellis of being a Communist agent. Later the Brazilian delegation made a formal complaint to FIFA, insisting that Ellis had “refereed the game in the interests of international Communism against western civilisation and Christ.” This was a tad harsh, although Ellis’s name remains a profanity in Brazil even today.

Ellis clearly enjoyed the powers refereeing afforded him, even if on occasion they didn’t amount to much more than the ability to control violent conduct on the football pitch. In particular, Ellis did not like linesmen who questioned his supreme control of a game. “Some men” – we are left in no doubt as to which man in particular he is referring to – “are at their best when they are in full command, but they are unable to play second fiddle.”

Having thus exempted himself from their lowly rank, Ellis goes on to explain how to be a good little linesman. “The first duty of a linesman should be to ensure he arrives early. The referee will want to give his instructions and explain his methods of control.”

In Ellis’s case the ‘methods of control’ were probably inspired by the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV. “A good linesman will follow instructions carefully. Some don’t!… Linesmen should appreciate that the signals they give are indications to the referee of some incident they have observed, but they should also appreciate that they do not give overriding decisions. A linesman should be an assistant referee and not an insistent linesman.” Despite this queasy stab at wordplay, there is no suggestion whatsoever from Ellis that this might merely be a playful reminder of who’s boss, a verbal nudge and wink. Instead, the dressing down of football’s flag waving minnows continues apace with a stern lecture on etiquette. “A linesman should never carry his flag unfurled or raise it just halfway. As a signal, the flag should be raised high and waved smartly.”

Should there be any lingering doubts as to Mr. Ellis’s regard for his ‘assistants’, one of the chapters in his book is called simply ‘Linesmen I Don’t Like’.

Those Brazilians never stood a chance.

The Battle of Berne

For a description of the match between Hungary and Brazil refereed by Ellis you’ll go far to better this one, penned by a contributor to Wiki. Where else will you find a goal described as “Julinho slalomed in to stroke a curling drive the ball knuckling into the top right corner of the net from the opposing side of the penalty box in one finest speculative efforts seen at the tournament”? What exactly was Csibor “foraging on the flanks” for? And what kind of stores did Brazil surge forward with at the end of the game?

The much fancied 1954 quarter-final between Brazil and Hungary was enthusiastically written about by the press covering the game as the “unofficial final”. For fans, organizers, and journalists alike the match’s ascent and buildout, had finally arrived. Hungary’s captaincy for the game with their talismanic captain Ferenc Puskás out injured was conferred upon József Bozsik, the era’s most gifted midfielder and the game’s nonpareil winger Zoltán Czibor spelled the injured captain Puskás at inside-left.

On June 27, 1954, even without their captain, the Magical Magyars summoned varsity capital effort and skill early on. After three minutes, Nándor Hidegkuti took receipt of the ball from the left side of the penalty box. In a scramble for it, half the Brazilian team funneled to the area with the quickest of speed where pandemonium reigned before Nandor Hidegkuti mightily plowed into the ball with violence through a wall of defenders to evoke high emotion in the 60,000 who had gathered.

Minutes later, Hidegkuti momentarily dwelled on the ball before lofting an arch from midfield, and inside-forward Sándor Kocsis outleapt the tight two-man marking to steer a long header into the net. 2-0 Hungary after 7 minutes.

The proud Seleção was ill at ease by the jarring pace of the immediate two scores put upon them by the Hungarians. Both teams strove in an attrition battle royal to stem the other’s advance and arrest developing plays through a policy that courted injury, unrelenting combative hard fouling that saw players clashing fiercely in contention for the ball. The game became erratic with continual interruptions after each free kick was awarded; an unheard of sum of 42 free kicks saw many piercing challenges lack respect and some were violently brutal. Of these, the tripping that felled forward Indio in the penalty area was converted from the penalty spot by Djalma Santos, 2-1.

By the 60th minute, the game was 3-1 and seemingly out of reach for Brazil, who did everything they could to keep within the match. Shortly afterwards, Julinho slalomed in to stroke a curling drive, the ball knuckling into the top right corner of the net from the opposing side of the penalty box in one finest speculative efforts seen at the tournament, 3-2. József Bozsik, a deputy member in the Hungarian parliament, taking umbrage and feeling that he was tackled unfairly, retaliated by punching Nilton Santos and soon both were in fisticuffs.

Brazil energetically surged forward with their remaining stores, but Didi hit the crossbar in what would be their last chance to draw level. Soon after, Djalma Santos put aside all ideas of playing soccer to pursue Czibor about the field livid in a fit of rage. In the final minutes of the game, Czibor was seen foraging peripherally on the flanks, found his bearing and supplied Sándor Kocsis with an aerial cross who firmly headed home the final score, 4-2.

The last moments of the game was little more than a running sparing match between the two great teams. Brazil forward Humberto Tozzi kicked Hungary’s Gyula Lorant prior to the whistle and was genuflect on bended knees not to be sent off by referee, Arthur Ellis, who doled out the game’s third red card. Nilton Santos and József Bozsik walked off the field after their explusion.

As the game concluded, the excesses and tensions on the field continued unabated off of it. Wild rumors broke and circulated that a spectating Ferenc Puskás allegedly struck Pinheiro with a bottle causing a three-inch cut, while most reports hold a spectator culprit and not the Hungarian captain. Hamstrung throughout the game, an incensed Brazil gave vent to frustration by having their fans, photographers, trainers, reserve players and coaches invade the pitch with the Swiss police powerless to impose rule on the tumult and disorder that followed. In the tunnel of the stadium, Brazilian players smashed the light bulbs leading to the Hungarians’ dressing room and ambushed the Magyars in their quarters where a melee in virtual darkness occurred, there broken bottles, fists and shoes were used as weapons. At least one Hungarian player was rendered unconscious and Hungary manager Gusztáv Sebes ended up requiring four stitches after being struck by a broken bottle.

Years later the game’s English referee Arthur Ellis commented, “I thought it was going to be the greatest game I ever saw. But it turned out to be a disgrace.”