More than twenty years on since the grizzly events surrounding Maurice Johnston’s signing for Rangers, JB Banal looks back in a spirit of reconciliation. After two decades of contemplation and reflection, he’d still like to string Johnston up to the ceiling by his nipples.

Simply appearing in the Celtic first team bestows on any player a modicum of fame. It might be of the fleeting or ephemeral variety – wasn’t it Andy Warhol who said that everybody should get fifteen minutes of playing in the Hoops? – but during his Parkhead career a footballer will become a well known face, not least because of the nature of the media in the West of Scotland.

If he is lucky, his exploits on the pitch will allow him a certain amount of longevity in the spotlight, endear him to the supporters and accord him a status akin to a minor deity.

If he is very lucky, he will transcend mortality and ascend into the pantheon of legends.

Alternatively, there are those who, for whatever reason, will find their particular chapter in the club’s history cursed by a stroke of ill-fortune or shamed by some misdemeanour that will blight their entry in the Alphabet of the Celts forever and give them a rare insight into the reason why Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner cancelled his subscription to Albatross Watcher’s Monthly.

Few would argue that Maurice Johnston staked his claim for an inclusion in both categories when, on Monday July 10th 1989, he signed for Rangers and finally ended his turbulent affair with the club for which had so frequently professed his undying love, an affair which in the eyes of the Celtic support saw him go from hero to villain back to hero – and then to the human incarnation of the contents of Beelzebub’s dustbin.

Johnston’s unrequited period lasted until 1984 when he was signed by Davie Hay.

His Celtic-Minded credentials were impeccable and his route to Parkhead had been a familiarly circuitous one. As a boy he had been sneaking into Celtic Park without his parents’ permission and was once even the subject of a ‘lost boy’ announcement when he went to a European Cup tie against Kokkola with some friends and ended up on his own (for the record, nobody claimed him).

A promising youngster, he was a regular in the Glasgow Catholic Schools Select and was offered professional terms with Partick Thistle in 1980 after impressing in a trial match against Celtic. Later the same night he was offered a similar trial with the Hoops but having agreed to go to Firhill he turned it down (trials were actually to become a regular feature during his playing career).

Peter Cormack gave him his break in the Thistle first team and he went on to score 47 goals in little more than two seasons before the Jags accepted an offer of £200,000 for him from Watford in November 1983.

Under Graham Taylor Watford reached the FA Cup Final, losing 2:0 to Everton with Johnston leading the line. Celtic lost the Scottish Cup Final to Aberdeen the same day and, as he put it in his biography, “I honestly felt as disappointed for them as I did for us. I suppose it was round about then that I was reminded of where my heart really lay.”

Despite his success at Watford he had heard a rumour that Celtic were willing to sign him if the price was right and in August 1984 he handed in a transfer request. It might also have helped that he had dropped a subtle hint when he attended a Glasgow derby in April, just a few weeks before the Cup Final. Interviewed live after the match by Radio Clyde’s Paul Cooney he announced that he’d always wanted to play for Celtic and that he’d walk from Watford to Parkhead for Davie Hay.

He got his wish in October. The news was broken to him on a midweek morning as the Watford players were gathering for a trip to Cardiff. He had been listening to Celtic songs blasting through the headphones of his Walkman when he was called into Taylor’s office and told he was being sold to Celtic for £400,000.

It was time for the love affair to be consummated, but the climax had more than a touch of burlesque about it.

Davie Hay and lawyer Mel Goldberg had arranged to meet Johnston and his agent Frank Boyd in Langan’s restaurant, an outrageously trendy London eaterie with an extortionate price list to match. The Celtic board were represented by director Jack McGinn, a man whose popular image on the Parkhead terracing was akin to a character in a Dickensian novel, the person keeping Ebenezer Scrooge’s wild spending in check. At some point during the meal – at which large amounts of lobster and champagne were consumed – a stripogram appeared, but the real entertainment came when the waiter proffered the bill.

After Boyd had offered to pay, Jack magnanimously insisted that he would pick up the tab for this one. It was a historic moment, after all. £400,000 was a record transfer fee for Celtic, as well as a figure the accountant probably thought he’d never see on a club cheque – unless he’d eaten some dodgy Welsh rarebit before going to bed.

Alas, Jack’s spirit of largesse promptly went up like a flambé when he saw that the night’s repast was going to set the assembled company back £480 and his solution to an embarrassing dilemma can only leave one wondering what on earth board meetings must have been like at the time. He offered to toss for it: heads or tails. Jack lost – then proposed best of three.

He lost that as well.

For public consumption the reason given for Johnston’s return north of the border was homesickness. Although this was partly true he was actually turning his back on more money (Spurs were willing to pay Watford £800,000) just to pull on the Hoops. He appeared on that Saturday’s Football Focus where a slightly incredulous Bob Wilson asked him why he was going back to Scotland. “I just want to play for Celtic,” was the reply.

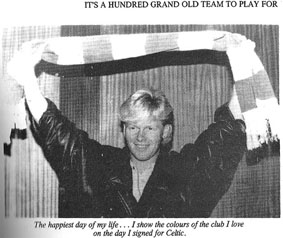

The formalities were completed on the Thursday evening when Johnston signed a two and a half year contract. He described it as, “The best day of my life” and at the time swore he would never leave, picturing himself signing new deal after new deal.

The financial figures involved in this transfer soon paled into insignificance as football entered the boom period of the 90s, but at the time most of us were stunned that a Celtic board – in the vanguard of the fiscal prudence movement long before it became either a buzz word for Gordon Brown or an economic necessity for clubs at the mercy of their money lenders – were willing to part with so much cash in a single deal.

Since taking over from Billy McNeill in the summer of 1983, Davie Hay had spent something in the region of £375,000 to acquire six players.

With Aberdeen and Dundee United enjoying an extraordinary spell of domestic dominance and Celtic exhibiting a worrying trend of losing crunch games it was a frustrating time to be a Hoops fan. The general feeling was that a lack of investment in the playing staff – despite having amassed quite a profit in transfer dealings during the previous few years – coupled with a willingness to replace genuine talent like Charlie Nicholas and Murdo MacLeod with journeymen pros was lowering the overall standard of the team’s performances and this was reflected in the average attendance at league matches, down by around 5,000 per home fixture. In truth, we looked well short of second best.

The Maurice Johnston transfer bucked the trend. It was a sign that the transcendentally optimistic among us took to mean that the fabled Celtic Biscuit Tin had finally been prised open and that the board were ready to meet the challenges that faced them head on through a heady mix of imaginative speculation in the transfer market and an aggressively bold approach to investment in playing staff.

To the sceptics, on the other hand, it was a desperate attempt to stop the exodus of punters from Parkhead who were finding alternative forms of masochism on a Saturday afternoon by blowing the profits accrued from selling players of genuine quality as well as the recently acquired sponsorship money derived from a three year deal with CR Smith.

Johnston went straight into the team for the Premier League match against Hibernian at Celtic Park on October 13th.

At Davie Hay’s suggestion he didn’t do his warm-up on the pitch so that the first sight the Jungle would have of him was when he ran on in the Hoops. As he puts it himself, “I’ll never forget that ovation until I breathe my last. It was so emotional I just couldn’t speak. Playing for Celtic is the most exhilarating experience I have ever known. Put it this way. By comparison, making love is like watching paint dry.”

He didn’t score in Celtic’s 3:0 win that afternoon – even refusing the chance to take a penalty in case he missed and spoiled the occasion – but it wasn’t long before he did open his account, a close range header in a 3:1 victory at Tannadice a week later.

It wasn’t long either before he was beginning to attract the kind of attention that suggested he was going to be fodder for the Glasgow tabloids as well as being a major irritant both to opposition defences and Celtic followers of a more traditional stripe in equal measure.

What passes for the paparazzi in the west of Scotland, together with their attendant hackers of lurid gossip, had lost a rich vein of copy when Charlie Nicholas left Parkhead to go to Arsenal. It’s true that the bold Charles was still good for the occasional headline, but at a remove of some distance, his exploits in the capital were unlikely to shift as many red tops as a target on their own doorstep.

With his dyed blond locks, earring, discrete white Porsche, and louche affectation for champagne Johnston was easily the man to step into Charlie’s sockless shoes. London had whetted Mo’s appetite for the high life and he wasn’t about to adapt to his new surroundings easily.

Towards the end of his first season with Celtic Johnston had scored five goals in seven appearances in the Scottish Cup and had helped the club to the Centenary Final, due to be played at Hampden on May 18th against Dundee United.

On the Wednesday before the match he found himself standing in the dock of Glasgow District Court as stipendary magistrate Robert Hamilton passed up the chance to be awarded the freedom of the City of Discovery by settling for fining the player £200, having found him guilty on a charge of resetting three stolen tracksuits worth £85. His co-accused, who had 13 previous convictions, was jailed for 60 days.

According to sergeant William Donaldson, he had spotted the pair “acting furtively” along with two others in a doorway adjacent to a sports shop up a lane in the city centre. They had been buying tracksuits that had been liberated from the shop and were apprehended in mid deal. The actual offence had taken place while Johnston was a Thistle player but by the time the story broke it was Maurice Johnston of Celtic who was making the headlines. It didn’t help that the team had to postpone their pre-Cup Final photo shoot as a result of Johnston’s appearance before the beaks.

On 17th March 1987 Johnston, this time in the company of his minder, was found guilty of assault on the premises of a popular Glasgow nightclub and fined £500 by Sheriff Archibald Bell QC.

The incident had happened in November 1986. The police arrested him before dawn on December 2nd and detained him as a guest at one of their bijou hotels in Stuart Street, where he checked out the following afternoon at 3pm.

Following his court appearance Celtic suspended him for a week and he missed two league games as well as Roy Aitken’s testimonial against Manchester United as a result.

Rumours that he was involved in recreational drug use – a common one was that he would customarily wear a long sleeved jersey to hide needle marks on his arms – eventually prompted Celtic to admit him to hospital on the pretext of a medical check-up (he was found to be free of any such substance abuse). There was also a paternity suit that was ongoing throughout his first spell in Glasgow and a seemingly constant barrage of headlines concerning his very public social life which kept him on the front pages almost as much as the sports pages.

Despite this, his contribution to the Celtic cause during his two and a half year sojourn in the Hoops cannot be understated. He formed an incredible partnership with Brian McClair – notwithstanding the fact that the two didn’t speak to one another off the pitch (Chalky and Cheesy?) – and in successive seasons between 1984 and 1987 they scored between them 42, 49 and 70 (!) goals.

For a player of slight stature Johnston was possessed of considerable physical strength which, when allied to his considerable bravery, sharp reflexes and composure inside the penalty area, made him a natural finisher in the style of Denis Law. He had a prodigious leap that made him highly dangerous in the air and he could complement this natural ability as a striker with a sure touch on the ball, an eye for a telling pass and tremendous reserves of stamina and energy.

He was a key player in the club’s winning of the Scottish Cup in ’85 and the Premier League on that never to be forgotten day at Love Street the following season. Johnston lost his boots in the chaos after the final whistle and did his lap of honour in a pair of black shiny walking shoes. “I still play the video of it at home in Nantes,” he recalled later, “and it always brings a lump to my throat. In fact I have treasured all the videos of my performances with Celtic because I will never forget how proud I was to play for them… I still love the fans of the club, no matter what they have said about me since I left.”

His record of 71 goals in 127 games (a strike rate of a goal every 1.7 games) stands comparison with some of the best forwards ever to have worn the famous hoops. Would that this was the end of his chapter in Celtic’s history. We lovers might have parted amicably and stayed good friends.

Johnston claimed that police harassment, sectarian abuse and the constant glare of the media spotlight were contributory factors in his eventual departure from Celtic in 1987. Davie Hay even hinted that, “There were people in the city of Glasgow who were setting out wreck his career with Celtic… He thought he was the victim of a carefully orchestrated hate campaign. I tend to think he was right.”

It’s impossible not to feel a degree of sympathy for someone who has sleazy tabloid reporters literally camped outside the front door of their house, of course, but I can’t help thinking there was a degree of contributory negligence involved.

The aforementioned biography – ghosted by Chick Young in 1988 and a particularly risible read, even by the appallingly low standards of this literary sub-genre – cites umpteen examples of victimisation. Yet there is not the slightest acknowledgement that perhaps a change of lifestyle or moderation of behaviour on the part of the player himself might have made some difference.

Little more than a shameless attempt at self-justification posing as the confessions of a football “character” – a Scottish euphemism for an immature, feckless individual incapable of foregoing a few nights of hedonistic indulgence for the sake of appearing to be too professional in his occupation – there are few passages in the book where Johnston acknowledges that perhaps he owed more by way of obligation to live up to certain standards demanded by those paying his wages.

The parting of the ways, when it came, was inevitably messy.

One newspaper story published in 1986 read: “Celtic superstar Mo Johnston is at the centre of a bizarre double agent mystery. Mo’s former agent Frank Boyd is believed to be negotiating a new £200,000 deal to keep the striker at Parkhead. But that came as a shock to Mo’s present agent – the flamboyant Bill McMurdo.”

The very mention of “the flamboyant Bill McMurdo” is enough to send a shiver down the spine, even today.

Not that “the flamboyant Bill McMurdo” could ever be accused of acting against the best interests of Celtic. A quick read at his CV would easily dispel any Celtic fan’s feelings of unease at the thought of flamboyant Bill being at the heart of any player’s contract negotiations: “Orangeman, freemason and fanatical Rangers supporter whose mansion at Uddingston, called Ibrox, is emblazoned with the red, white and blue of Unionism, with one room set aside as a shrine to Rangers… He was also a leading light and founder of the Scottish Unionist Party, which is violently opposed to the Anglo-Irish Agreement.”

To be fair to him, McMurdo never let his political or religious principles get in the way of making a few quid and his players all appear to have great respect for him, regardless of their persuasion.

Club directors, by contrast, saw him in a slightly different light and he was at one time or another banned from Fir Park, Tynecastle and Celtic Park, where Jack McGinn once wrote to inform him that he was persona non grata.

After an attempt to sue Brian McClair over the proceeds from a sportswear sponsorship deal, presiding Sheriff Andrew Lothian dismissed McMurdo’s case with the words, “I cannot accept Mr. McMurdo as a credible witness.”

He was known to Celtic fans simply as Agent Orange.

Johnston later admitted that the newspaper story was, in its essence true, and that he had been stringing Boyd along while dealing with McMurdo.

Boyd, as it happens, was still involved in the deal as a negotiator for Celtic. Call it a wild hunch, but once we realised who was doing Mo’s bargaining we resigned ourselves to losing his services at the end of the 1986-87 season and by March it was obvious that his time had come.

There was a brief hope of a reconciliation when the board dispensed with Davie Hay – a week after giving him their blessing to spend £425,000 on Mick McCarthy and smash the club’s wage structure into the bargain – and appointed Billy McNeill, but the new boss appeared to be in no mood to coax the player into staying: “As far as I’m concerned Mo Johnston can sign for whoever he likes.”

Within a few days he did just that and signed for Nantes. The love affair was over. Custody of the tracksuits was uncontested.