An extract from a chapter of Tom Campbell’s excellent book Celtic’s Paranoia – All In The Mind? entitled “Celtic and Scotland” in which the author discusses the puzzling lack of international recognition afforded to one of the game’s all-time greats by the SFA.

Until the World Cup of 1954 in Switzerland, Scotland did not have a manager and, in fact, the first manager (Andy Beattie) quit abruptly halfway through that tournament and returned home to leave the thirteen players to fend for themselves. The squad went to Switzerland without a backup goalkeeper and at the first training session one player, noting that the players had been forced to practise in their club strips, commented: ‘We look like liquorice all-sorts.’ The expedition turned out to be a thoroughly amateurish exercise, leading inevitably to a 0-1 defeat by Austria and a humiliation from Uruguay by 0-7. Among the criticisms later levelled was the accusation that more SFA offkials were present on the jaunt than players. Neil Mochan, the Celtic centre forward, was chosen for the event and commented later: ‘It was treated more like an end-of-season tour than anything else.’

Later advertisements for the position of manager suggested that the SFA had still not wakened up to the reality of the modern age as they suggested the post could be carried out successfully ‘on a part-time basis’. The early ‘managers’ still had to deal with the members of the Selection Committee who were most reluctant to give up any of their power or influence. Ian McColl (ex-Rangers) apparently was unable to announce his side for one match until the selectors had voted between Willie Henderson and Alec Scott both of Rangers. The latter had been a regular for Scotland at outside right but had recently lost his place in Rangers’ team to the newcomer Henderson. Rangers were able to solve that particular dilemma by transferring Scott to Everton and retaining Henderson.

It is generally believed that the first Scottish manager to insist on his right to pick the side was Jock Stein, when he took over for a few months in 1965 to help the SFA out in a crisis situation.

Thus, if any bias was shown against Celtic players, the blame lay for years with an unwieldy committee, and later by individual Scottish managers. Some Celtic supporters insist that such a bias has continued and exists even at the present. Perhaps it is time to examine the facts objectively.

The most obvious example of the existence of such discrimination lies in the shabby treatment of a genuine Celtic hero, Jimmy McGrory. Signed by Celtic from St. Rochs Juniors in 1921, McGrory, a shy youngster, took some time to adjust to the senior game and was farmed out to Clydebank in 1923; but, after returning to Celtic Park for the start of the 1924/25 season. he embarked upon a magnificent career as a centre forward.

He was a one-club man, a jersey player, totally loyal to Celtic and their supporters, who personally resisted efforts by the club to sell him to Arsenal for a British record transfer fee in 1928. In the 1920s and 30s football was more physical than at present, and the stocky McGrory, although on the short side for the spearhead of the attack, was frequently the target of crude tackles and rough treatment. Despite that, and the inevitable toll of injuries, he played for Celtic until 1937 averaging almost a goal a game for fifteen seasons, He ended up with the amazing total of 410 goals in 408 league matches, a figure which includes twelve goals for Clydebank, and the overall tally of 550 goals in the top flight of senior football. It was truly an incredible career as, uring many of those seasons, Celtic were an inconsistent side and McGrory frequently lacked genuine support up-front.

The major surprise lies in the meagre number of caps won by this legendary performer. Jimmy McGrory played only seven times for Scotland, despite smashing almost every scoring record in British football, and in those seven games he scored six times.

The issue was clear-cut to partisan Celtic followers; they argued that there was a bias against McGrory simply because he was a Celtic player. On the other hand, apologists for the SFA committee which chose Scotland internaal sides could argue that McGrory was unlucky to be a near-contemporary of Hughie Gallacher.

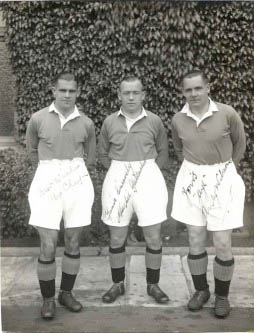

Hughie Gallacher (centre) pictured here in his Chelsea days flanked by two other Scotland players, Alex Cheyne (left) and Andy Wilson (right).

This latter argument is worth considering in some detail.

Hughie Gallacher was undoubtedly one of the most gifted strikers ever to play for Scotland. After his start with the strong Airdrie side of the 1920s Gallagher’s career flourished following his move to England and his appearances with Newcastle United, Chelsea, and Derby County. In fact he was a member of the most famous of all Scottish sides, the Wembley Wizards who thrashed England by 5-1 in 1928. The ‘Anglo’ also had the advantage being the man in possession, having won his first cap in 1924, at the time when McGrory’s career was just starting with Celtic. Gallacher, a scorer at international level, went on to make twenty appearances for his country.

I would have to agree reluctantly with the SFA’s position with regard to the dilemma posed by having two such gifted players competing for the position. In addition, this was a time when international matches were rationed, the three fixtures against the other home countries being the norm. Gallacher, a man who had never let Scotland down, was still at his prime in the period when Jimmy McGrory was emerging as a star in Scottish football and deserved to be chosen more frequently than the Celt.

However, consider what happened when the veteran Gallacher’s talents began to erode with age and the contributory factor of a dissolute lifestyle. Gallacher made a further five appearances for Scotland during the 1930s, four in the home internationals and one cap against France awarded in an unimportant European tour. Such loyalty by the selectors was understandable and commendable.

By the early 1930s Jimmy McGrory was at the height of his powers. He scored two goals to help win the replayed Scottish Cup final against Motherwell in 1931, having inspired Celtic to an unlikely recovery in the first match. He scored the only goal of the1933 final also against Motherwell despite losing two teeth in the opening minutes of the match. And notably, in a rare appearance against England at Hampden Park in 1933 McGrory scored both Scottish goals in a 2-1 victory; the second, when he crashed the ball past Harry Hibbs, being generally recognised as the start of the famous ‘Hampden Roar’ as 134,170 Scots celebrated.

Despite his outstanding form for Celtic (and Scotland), McGrory, the logical successor and heir-apparent to Gallacher, was capped only six times in the 1930s and had to share the representative honours with a variety of men: Jimmy Fleming (Rangers) who played against England in 1930; Benny Yorston (Aberdeen) chosen against Northern Ireland in 1931; Barney Battles (Hearts) fielded against Wales in 1931; Neil Dewar (Third Lanark) who played against England in 1932 and Wales in 1933; Willie McFadyen (Motherwell), selected against Wales in 1934; Jimmy Smith (Rangers), chosen against Northern Ireland in 1935; Matt Armstrong (Aberdeen), fielded against Northern Ireland and Wales in 1936; and Dave McCulloch (Hearts and Brentford) who was preferred in 1935 against Wales and in 1936 against England. McCulloch’s appearance against England must have been a particularly bitter blow for the veteran McGrory as it meant that the greatest scorer in British football was denied a last chance to play at Wembley Stadium – and during a season in which the Celtic player had scored fifty league goals!

The purpose of the above paragraphs is not to disparage the other players chosen for the internationals: for example, Neil Dewar was a prolific scorer at club level for Third Lanark; Jimmy Smith ended up as Rangers’ all-time highest scorer in league matches with 225 (excluding the war-games); Jimmy Fleming, a versatile player who often played as a winger, ended up with a tally of 177 league goals for Rangers; and Willie McFadyen, as a member of a classic Motherwell side, still holds the Scottish record of fifty-two goals in a single season.

However, any objective historian of football would have to admit that none of the men who shared the representative honours with McGrory during those seasons was the equal of the Celtic player in terms of ability, effort and achievement.

Only one other argument in favour of the selectors might be forwarded: the fixtures against Wales and Northern Ireland were regarded as relatively unimportant, and were frequently used to reward players and clubs. Sometimes the selectors – usually seven in number and drawn from various parts of Scotland – were capable of ‘regional voting’ to encourage local interest throughout the country. This might well have accounted in part for the selection of the two Aberdeen players (Yorston and Armstrong) in preference to McGrory. As the selectors met infrequently and probably saw only those fixtures in which their own clubs were involved, a disproportionate influence was exerted by the SFA secretary. George Graham was appointed to the post 1928 and no doubt saw the advantage in ‘regional voting’ as a sure-fire method of promoting his own career within Scottish football.

One outstanding – and influential – player who championed McGrory’s cause was the Rangers inside forward Bob McPhail. He played against McGrory in many Old Firm clashes, and alongside him in several internationals; it was his pass that provided the chance for one of McGrory’s goals against England in 1933. McPhail was critical of the selectors’ repeated failure to chose McGrory, and it was rumoured that he had gone as far as to withdraw from one international ‘through injury’ as a protest.

In view of the oft-repeated claims that Rangers are ‘a Scottish club’ and Celtic are ‘an Irish club’, it is ironic to note McPhail’s own admission in his excellent autobiography Legend: Sixty Years at /brox (Edinburgh, 1988) that he was actively encouraged by his club manager to withdraw from the national side in order to conserve his energy for important Rangers matches: ‘Bill Struth made sure I suffered no financial loss any time I had to pull out of an international squad.’

McGrory himself, of course, was a shy, retiring type of personality and a genuinely modest individual; he would never have resorted to complaining about his treatment at the hands of the selectors. Perhaps this diffidence contributed to the meagre total of caps won by this most whole-hearted of all players although he was hurt, as this excerpt from his own autobiography A Lifetime in Paradise (London, 1975) suggests: ‘Despite my goal-scoring feats the SFA overlooked me for the game against England at Wembley – my last chance to play on that famous ground which had always eluded me. But, as I’ve said, we Celts were used to being overlooked in those days, unfair as it was. It is very refreshing in these modern times [1975] to see the club so well represented in the Scottish team whose jersey I was always proud to wear.’

‘Jaymak’, a columnist for the Evening Times, pointed out on 1 April 1936 that McGrory’s surprise omission ‘has brought me many expressions of indignation’ and cited one letter as an example: ‘ … up till last weekend he was a certainty. What went wrong? There is no doubt that he is showing as good, if not better, form than any of the players chosen. It seems to me that the selectors are determined McGrory shall never play at Wembley.’

Some apologists for the SFA had suggested that McGrory, by then in the veteran stage, had been rejected this time on account of his age and ‘Onlooker’ attempted to refute this argument in the Glasgow Observer of 4 April 1936: ‘Age becomes a decided handicap, especially in soccer, when one is playing against such youthful talent as [Bob] McPhail, who played with Airdrie who won the 1923/24 Scottish Cup final. Seems this handicapping according to age only applies if those concerned wear the green-and-white jerseys, for McGrory didn’t become a Celt until the following year.’ The columnist’s argument is weakened somewhat by the fact that Jimmy McGrory was eighteen months older than Bob McPhail, although the latter had indeed broken through as a senior earlier.

It is interesting to note that Bob McPhail also never played at Wembley.

The Ranger played five times against England at Hampden Park and it is believed that he was encouraged to withdraw from some international matches against England because the stamina-draining effects of the famous Wembley turf might have reduced his efficiency for Rangers in forthcoming Scottish Cup final appearances (in 1930, 1932, 1934 and 1936).

Nothing can convince older Celtic supporters that Jimmy McGrory was not treated shabbily by the Scottish selectors, and that the neglect was due solely to the fact that he played for Celtic. The Evening Times printed an anonymous poem submitted to its ‘Gossip and Grumbles’ column on 6 April 1936:

If he hadn’t played for Celtic

and he’d worn the jersey blue,

I’m sure he’d be at Wembley

to the delight of me and you.

But, because a good man’s Irish,

sure it’s always been a sin.

Why! They wouldn’t give us credit

for our champion Jimmy Quinn.

Long life to you, McGrory,

you’re the best we’ve ever seen.

You’re the finest centre forward

who wore the white-and-green.

Talking of bias what about the treatment of Kenny Dalglish by Wullie Ormand. Sitting at 59 consecutive caps he needed 1 more to equal the record of George Young. Of course he was not selected to play, not even as a substitute thus denying him a change to beat the record in the next game. I could never understand why he played for Scotland again.

I meant 49 caps