As part of his ongoing therapy necessitated whenever he hears the name mentioned in the news, Manfred Lurker looks back at the infamous night Atletico Madrid collected together all the muggers they could find from the dark alleyways of the Spanish capital and sent them over to Celtic Park to contest a place in the 1974 Champions Cup final.

By the time Celtic embarked on the European Cup campaign of 1973-74 only three of the players who had triumphed in Lisbon six years earlier were still regular members of the team. Billy McNeill was still a stalwart at the heart of the defence while Bobby Lennox and the mercurial Jimmy Johnstone could still hold down a place in the forward line.

Nevertheless, big Jock had once again put together a side which looked as if it was on the verge of European greatness. Danny McGrain, Jim Brogan, Davie Hay and Pat McCluskey had all established themselves in the defence. Not only were they tough and uncompromising, they could use their silky skills to trap, control and pass any winger in the country.

In midfield Jock could call on George Connelly, Steve Murray and a bloke called Dalglish (whatever became of him?) and in attack, to add to the lightning pace of Lennox and dribbling skill of Johnstone, he had the poaching instincts of Harry Hood and the gumsy grin of Dixie Deans.

In the first round of that season’s competition Celtic eased past TPS Turku of Finland, who played like TPS Turkeys and who were gobbled up in a 9:1 aggregate defeat which could easily have ended up 90:1.

Danish champions Vejle BK were made of somewhat sterner stuff and managed to earn themselves a 0:0 draw in Glasgow after Celtic turned in what many described as one of our worst European performances ever. By comparison with what was to come during the 80s and 90s it was probably a class show! It was left to Kenny Dalglish to score in Denmark for a 1:0 aggregate victory.

The quarter-final produced a cracking match against the previous year’s nemesis, FC Basel. The Swiss won the fist leg in their home stadium by 3:2. They then showed they were no cuckoos by coming back from 0:2 down at Celtic Park to draw level. Tommy Callaghan put Celtic in front again but there were no more goals in a nail-shredding finish to the regulation 90 minutes. Stevie Murray headed the decisive goal eight minutes into the first period of extra time, which was enough to see the Celts looking forward to their fourth semi-final in eight years.

Bayern Munich were drawn to play Ujpest Dosza and so, as fate would have it, Celtic were to play against Atletico Madrid.

At the time not a great deal was known about Atletico other than they had been living in the shadow of city rivals Real for years. However, alarm bells started ringing when it was revealed that their coach was the infamous Juan Carlos Lorenzo.

Lorenzo had been in charge of the Argentinian national squad at the 1966 World Cup who had been branded ‘animals’ by Alf Ramsey after their quarter-final match against England at Wembley and Atletico’s arrival in Glasgow for the first leg of the European Cup tie did little to dispel growing unease that we were in for a similar kind of Donnybrook.

The Madrid players had been limbering up for the Wednesday night’s game by kicking the seven shades of shit out of each other during a training session. Things got so out of hand that two of their Argentinian contingent had a square go in the middle of the pitch, pictures of which appeared in the Tuesday night’s evening paper.

In front of 70,000 at Celtic Park on Wednesday 10th April 1974 the teams lined up as follows:

CELTIC: Connaghan, Hay, Brogan; Murray, McNeill, McCluskey; Johnstone, Hood, Deans, Callaghan, Dalglish.

ATLETICO MADRID: Thug; Psycho, Punch; Spit, Hatchet, Bludgeon; Hammer, Thump, Wallop, Gouge, Axe-Murderer

The unlikely – and downright unlucky – referee chosen to officiate that evening was a hapless Turkish gentleman by the name of Dogan Babacan. He looked a bit like Arthur Lowe’s officious bumbling bank manager character, Mr. Mainwaring, from Dad’s Army. He probably felt greatly honoured being entrusted with such a major football spectacle. Little did he know, he stood as much chance of controlling this game as the last referee at the Rome final of 46 BC, Christians FC versus Lions United.

The first name was in Mr. Babacan’s notebook after only seven minutes following a vicious assault on Jimmy Johnstone. It set the tone for the rest of the evening’s fiasco.

Babacan got a chance to practice more Spanish a minute later. Jinky’s bruises from the game against Racing in Montivideo seven years before had just cleared up the previous week when a lump nut by the name of Ruben Diaz – who had actually played in that match – decided to renew his acquaintance with the Celtic winger. It was the first of his many assaults that night.

With the crowd already worked up into a frenzy at the sight of the atrocities being committed by the Atletico players, Celtic had a goal disallowed after ten minutes. It did little to dampen an atmosphere which had taken a decided turn towards the volatile.

Neither did the antics of Atletico Madrid. It became clear very quickly that the remaining eighty minutes of the match was simply going to be replay of the first ten. Name followed name into the ref’s notebook, which he was forced to swap at half-time for a 200 page ring-binder.

Eventually, having flashed the yellow ten times, he sent off the first Atletico player midway through the second half. By this time Dixie Deans had been substituted and was soaking his bruises in the bath. Hearing the roar of the crowd which greeted the dismissal of the Spanish player and thinking it might be a Celtic goal, he decided to get out of the bath to investigate. Wearing nothing but a towel he was met in the corridor by an irate Argentinian – who proceeded to give him a kick on the shin as he walked past!

Meanwhile, back on the pitch things were degenerating quickly. Jinky was being kicked around like a discarded lager can as well as being treated by his opponents like a red-haired punchbag. Dalglish and Hay were also being singled out for special attention.

It was all too much for poor Mr. Babacan who must have wished he was somewhere on the Russian Front rather than at Celtic Park that night. By the end of the game Atletico had been reduced to eight players, five of whom, including the ‘keeper, had been booked.

They had achieved their 0:0 draw but they weren’t finished yet. On the way up the tunnel Jimmy Johnstone was brutally assaulted yet again. It was the final provocation for the Celtic players. A punch-up ensued which had to be sorted out by Strathclyde’s Finest.

Next morning a picture appeared on the back pages of the papers. It featured Jimmy Johnstone semi-naked showing off his bruises. He looked as if he’d been battered for a fortnight with a hammer then given a good rub down with sandpaper.

Although the first leg had been shown live on Spanish TV, Atletico quickly got to work after the match with their propaganda campaign. They claimed that they were the victims of a concerted and orchestrated campaign of abuse at the hands of Celtic, the referee and, of all people, the Glasgow Police. They alleged that the polis had come into their dressing room and beat up their players. It was preposterous, as anyone who has ever had any contact with the Glasgow Police will know. As was the assertion that Celtic had bribed the referee. If only the Spanish people had realised how difficult it was to prize open Desmond White’s Biscuit Tin to pay our own players never mind find extra money to give backhanders to the ref.

The story of the second leg is recounted thus by Graham McColl in his book “Celtic in Europe”:

It was suggested then, and in the years since, that Celtic should simply have scratched from the tournament and walked away, but that was never a realistic option. They did not have to look far into the past to see the severity with which UEFA might punish a club that threatened to pull out of a fixture. Benfica, prior to their 1965 European Cup final with Internazionale, had threatened not to take part in the match unless it was switched away from the San Siro stadium in Milan, the home of their opponents. The promise of retribution from UEFA was swift and sharp. In the vent that Benfica did not turn up, stated UEFA, they would fine the Portuguese club a sum approximating to £40,000; a figure composed of a fine plus compensation for lost gate receipts, a substantial chunk of which were due to find their way into the Swiss vaults of European football’s self-satisfied governing body.

UEFA clearly viewed the merest hint of dissent against them, or any threat to their projected income, to be of far greater import than a club tarnishing the image of the game itself, as had been the case with Atletico at Celtic Park. In 1974, a decade after that threat against Benfica, a projected estimate of the financial punishment Celtic might expect from UEFA was in the region of £1000,000; a sum pf considerable magnitude and one greater by far than any transfer fee the club had paid out up until that time.

UEFA might also have imposed a ban from European football. Celtic only had to look as far as Glasgow Rangers for an exampe of that: just two years earlier Rangers had been banned from defending the European Cup Winners’ Cup after their supporters had invaded the pitch at the final in Barcelona.

It had been in the gift of UEFA to take action against Atletico and they had failed in their duty to act for the good of the game. It is also no exaggeration to state that that UEFA’s insistence on Celtic travelling to Madrid placed the lives of the players in serious danger. ‘It was a nightmare in Madrid from when we got off the plane until we left,’ commented Jimmy Johnstone. ‘It was just hatred. At the airport we had the police and the army to protect us and the escorted us back and forward to and from training sessions. we had the army behind us and the army in front of us going to training. At the hotel there were plain-clothes policemen walking about, gunned up. We were told beforehand that they were there for our own protection.’

The Celtic team arrived at Atletico’s stadium on the banks of the Manzanares river for the second leg to find that it was ringed by 1,000 police officers with a mounted division in operation to keep at bay the Atletico supporters, whose inferiority complex at living in the shadow of Real Madrid had been inflamed to hellish proportions by the propaganda of their newspapers, which had written up the events in Glasgow in such a way as to make Atletico appear to be the victims of harsh treatment on Celtic’s part. Spain in 1974 was a country that had for four decades been in the grip of a fascist dictatorship, headed by General Francisco franco, and newspapers were tightly controlled to report stories along strict nationalistic lines.

Water cannon and tear gas were part of the armoury deployed by the police to keep the crowd at bay, and Jimmy Johnstone remembered distinctly the moments when the frothing Spanish crowd were finally given the chance to release their pent-up emotions on sight of the Celtic players. ‘When we got to the ground, it was a cauldron,’ he said. ‘we went out before the game to kick the ball about and you should have heard them! I had never seen as much hatred in my life.’

After just three minutes of a warm-up, the Celtic players had to evacuate the playing field for their own safety. it was already clear that regardless of the various pompous statements that had been issued by UEFA, this was never going to be a game played under normal sporting conditions. UEFA had warned Atletico as to their future conduct but the hostile atmosphere generated by that second leg meant that Celtic had next to no chance of winning the tie.

The Celtic team that took the field in Madrid under the most adverse conditions was: Connaghan, McGrain, Brogam, McCluskey, McNeill, Hay, Johnstone, Murray, Hood, Dalglish and Lennox.

The threat of being shot had, unsurprisingly, a severe effect on Johnstone’s game and, once the match got underway, he and his team mates discovered that the referee too had been affected by the atmosphere of intimidation. ‘The Atletico players were just at it all night,’ Johnstone explained. ‘any opportunity they got they were nipping you and spitting on you and the referee was turning a blind eye. He was looking at the crowd and was probably thinking, “I’m not getting into any bother here”. They were nutters. That wasn’t football. That was the sadder side of football. Football is a great game, a lovely game; it’s greta to play in matches where there’s a lovely atmosphere and you meet lovely people. UEFA should have given us the tie, without a shadow of a doubt. It was riduculous that we had to go and play over there. There were a number of Argentinians in that team and big Jock met the Argentinian manager at the World Cup later that year and he said that if there had been dope testing done on that team then there would have been about five of them that would have tested positive for using stimulants in that game. They were just mad. That wasn’t football at all. They were just animals really.’

Bobby Lennox also remembers well that visit to Atletico, and playing in front of their 65,000 supporters, stirred into a state of dementia. ‘That’s the noisiest away crowd I’ve ever heard. They were really screaming and bawling. They hated us. The team that beat us in Madrid should never have still been in the tournament. Had they come and played football against us in Glasgow we would have beaten them.’

An article in World Soccer provided as good a summary of events as any: What a shame it is a team from Madrid who have to leave the fans with such cruel feelings and agonising memories. Up until the Parkhead first leg fiasco Madrid had always thrown up visions of the legendary Real with di Stefano gliding through the centre, Gento sweeping magnificently down the wing, Puskas and his lethal shooting power, the towering defensive work of Santamaria. One giant, ugly, clumsy foot has trodden these cherished memories well and truly into the dirt.

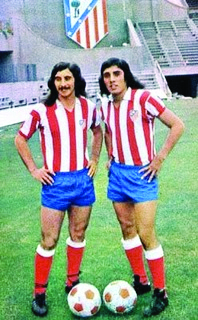

Above: The winners of the Atletico Madrid Freddie Mercury lookalike competition for 1974 were Ruben Ayala (left of picture) and his mate, who wowed the judges with their cover version of ‘I Want To Break Free’ which they titled ‘I Want To Break Jimmy Johnstone in Three’. Ruben Ayala had the longest hair at the 1974 World Cup in Germany. 17.4 cm.

Postscript

When Celtic shared a group with Atletico in the UEFA Europa League in 2011 Billy McNeill was asked about his memories of the ‘74 match by the Spanishmedia. His response wasn’t quite what they’d wanted to hear. Sandy Jamieson reported on the Atletico players’ fightback:

Billy McNeill’s description of the 1974 Atletico Madrid side that kicked Celtic out of the European Cup semi-finals as “Scum” has provoked a mixed reaction in Madrid. The official response of the Spanish club has been injured innocence and comments like “We do not understand why they are harping on about a match played 37 years ago. We would rather concentrate on the present.”

But one of the players from that towsy first leg match in Glasgow in the 10th April 1974 has come out with a more spirited direct response. Panadero Diaz, the giant Argentinean centre half was one of the three Atletico defenders sent off during the game, after a particularly atrocious tackle on Jimmy Johnstone, who as Panadero honestly admits “was leading me a merry dance and driving me mad”. Panadero describes his offence as kicking Jinky in the ribs and accepts he deserved to be sent off. But he defends the overall conduct of his team. “In that era teams played much harder and more physically than they do nowadays” He accepts Atletico were a hard team but emphasised that Celtic were no saints. And as one tough centre half to another he said “McNeil might not have forgotten what we did to them, but we have not forgotten what he did to us.”

Panadero made it clear he resented the title of ‘scum’ and claimed that Atletico Madrid of that era were one of the finest teams in the world, on a par with Barcelona and Real Madrid. And in one sense what he says is correct. In the European Cup Final against a Bayern Munich side, containing world class stars like Beckenbauer, Brietner, Hoeness, Maier and Muller, Atletico were one minute away from winning the European Cup. And in Bayern’s absence they represented Europe in the Intercontinental Trophy beating Copa Libertadores champions Independiente over two legs to be crowned as “World Club Champions”

So how justified is Billy McNeil’s use of the strong phrase “scum”.

I am aware that few if any Celtic supporters under the age of 50 will have any direct memory of that torrid encounter from 37 years ago but there must be still many of the 70,000 plus spectators other than myself who have vivid memories of an unforgettable evening. 2 years previously Celtic had lost at the same semi-final stage to Inter Milan, on penalty kicks and most of the enormous crowd were confident that this time, against Atletico they would go a stage further and reach their third European Cup Final. As I took my place in the jungle, I knew Atletico would be no push-overs. I also knew that the Atletico Manager Juan Carlos Lorenzo, El Toto, was a ferociously competitive Argentinean, the manager from the 1966 World Cup team that had been called ‘animals’ by Alf Ramsey, and that he was famous for using psychological pressures on his players to ensure they stayed winners, at any cost.

37 years on Panadero Diaz describes Lorenzo as “a monster” and remembers Lorenzo telling him well before the game to let his beard grow long and to show his teeth, the better to frighten the Celtic players

Even so, along with the rest of the capacity Celtic Park crowd I was amazed at the degree of ferocity unleashed by Atletico throughout the 90 minutes. I have never before or since seen such sustained brutality practised by a whole team for a whole game. The Turkish referee booked 7 of the Atletico players and sent 3 of them off, including Panadero Diaz. All for tackles that would have been criminal assault in any other context. The Celtic players were not physically intimidated and while they responded physically they did not lose the place. But incredibly it was their rhythm and concentration rather than Atletico’s that suffered most from the constant stoppages, and even the ever increasing numerical superriority could not be turned to their advantage. The game ended goal-less, the restrained Celtic crowd booed the Atletico team off the pitch, and mayhem broke out in the tunnel as a score or two was settled, reputedly with the help of the Glasgow police.

Thanks to the wonders of You Tube the worst highlights can be seen by googling Celtic v Atletico Madrid 1974 so if you weren’t there, take a look and marvel. Three of the tackles on Jimmy Johnstone will horrify any sensitive soul, and remind everyone that the wee man was not only highly skilled but extremely brave, to carry on taking such abuse without ceasing to run at them. While universal outrage at the degree of cynical violence practiced by Atletico swept the whole continent, UEFA took no other action bar banning the three players sent off from the second leg and fining Atletico a derisory amount. Some people urged Celtic to pull out of the second leg but I think the decision to play was the right one, even if the outcome was a tame defeat.