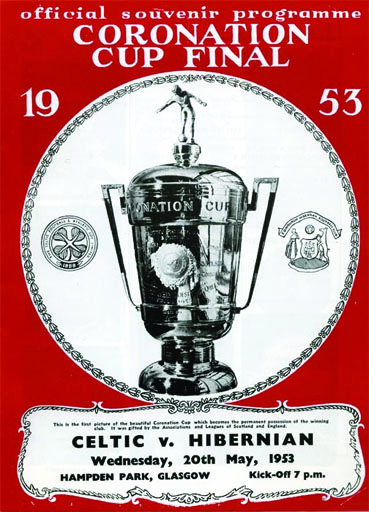

On May 20th 1953 Celtic wrote another chapter in our history with an unlikely victory over Hibs in the final of the Coronation Cup. Rhapsody in Green is a lesser renowned but still hugely entertaining book by Tom Campbell and Pat Woods. In a chapter entitled ‘The Impossible Dream’ the authors describe the Coronation Cup Final and the reaction the victory got from supporters. All together now, “Said Lizzie to Philip as they sat down to dine…”

A sportwriter of the period once dismissed the Celtic supporters’ enduring optimism in these words: “Celtic supporters? If Celtic get two corners in a row they’re happy roaring their heads off and enjoying themselves.”

What would he have thought watching the terracings fill up before the Coronation Cup final – and seeing that same Celtic spport still exulting in the unlikely conquests of Arsenal and Manchester United?

The mood was one of jubilation; nobody on the King’s Park terrace entertained the possibility of defeat – even against Hibernian on top form. And yet ten days previously only the most rabid fan would have considered that Celtic should have been competing in the tournament.

Against Arsenal on 11 May Celtic had started slowly but, after Evans took the game by the scruff of the neck, the whole team responded magnificently. The Celtic support reacted with noisy disbelief, and kept up a constant roar of encouragement; players out of touch for weeks started to string together a few passes, and Bobby Collins scored directly from a corner on the right after 24 minutes.

Most of the 59,000 crowd expected the English champions to respond but Celtic continued to exert pressure; indeed, they came on to a game in the second half that had veteran supporters reaching far back to recall a similar performance. Cool goalkeeping by Swindin kept Arsenal in the game, including a save at the feet of Alec Rollo – and this was in a time when full backs were conditioned not to cross the half way line. Celtic’s victory was assured by a splendid display from their half backs, Evans, Stein and McPhail.

Bobby Evans could be considered the best wing half in Britain, and nobody played with greater spirit and enthusiasm for Celtic for so long with such little reward; against Arsenal his colleagues for the first time played up to his standard, and he revelled in the occasion.

John McPhail, never fully fit after 1951, had been moved back to left half, and was playing reasonably well there until the Coronation Cup; then his natural skill, allied to cool professionalism, came to the fore again. Jock Stein exuded confidence at the heart of defence, even against the dangerous Cliff Holton, who had averaged a goal a game during the previous season. One Celtic supporter described the feeling of watching this match: ‘It was like finding a five-pound note in an old jacket pocket. You don’t ask any questions; you just accept it.’

In the semi-final Celtic faced Manchester United at Hampden before a crowd of 73,466, and again responded to the mood of their spectators. It was a triumph for speed and directness in attack, and determination and concentration in defence. United tried to play a close-passing game that foundered on Evans’ superb anticipation and Stein’s forceful interventions.

Once again Stein was faced with a formidable opponent in Jack Rowley, a veteran but free-scoring leader. Rowley was a centre forward in the traditional mould, hard, direct and uncompromising in the pursuit of goals. Stein decided to meet strength with strength. W. M. Gall of the Scottish Daily Mail accused Celtic’s pivot of ‘being a bit hard at the outset on Saturday on Rowley, who never quite recovered from a leg injury and latterly went to outside left’. (18 May 1953)

Two splendid goals – a shot from the edge If the box by Peacock in the first half, and an exciting breakaway by Mochan from midfield to slip the ball past Crompton – gave Celtic a narrow 2-1 win.

Hibernian had reached the final much less surprisingly, defeating Tottenham Hotspur in a replay, with Reilly getting one of his famous late goals to oust the Londoners. While Celtic were scraping past Manchester United at Hampden, Hibernian were toying with Newcastle United at Ibrox. Ronnie Simpson and a resolute Newcastle defence were helpless against the raids of Hibs’ forwards. Two goals by Eddie Turnbull, and one each from Lawrie Reilly and Bobby Johnstone, ensured a 4-0 rout of the Englishmen.

Celtic’s hopes were dented before the final with the realisation that Charlie Tully would be unable to play. This was a blow, because the had performed exceptionally against both Arsenal and Manchester United, and he had made both Celtic goals in the semi-final before pulling a

muscle in the closing minutes. After much deliberation his chosen replacement was Willie Fernie, a highly skilled player but still regarded as too selfish on the ball.

One other thought, however, encouraged Celtic. For all their undoubted excellence and flair, Hibernian had not enjoyed much success in cup competitions, their last trophy won being the wartime Southern League Cup

Still, Hibernian would start as favourites, a testimony to their prowess and the conviction among the bookies that lightning was unlikely to strike three times in the same place. Andrew Wallace felt that, if Hibs scored first, ‘Celts will be swamped by the high brand of skill which riddled the Newcastle United defence on Saturday.’ (Scottish Daily Mail: 20 May 1953)

The largest crowd for the tournament flocked to Hampden to see the final. The attendance was later announced as 117,060 but another 10,000 ere estimated to have been locked out when the gates were closed. The Kings Park end of Hampden had been filling up for more than an hour before the kick-off, and was dangerously overcrowded. Attempts to distribute the crowd more equitably were unsuccessful, and so the authorities decided to stop further admission.

Before the match the newspapers had guessed that the attendance would be close to 80,000, but the prospect of a Celtic appearance in the final, the appeal of Hibernian, and a pleasant sunny evening resulted in the late surge of interest.

The weather was a factor in making the final a memorable encounter; it had rained in Glasgow for part of the day but the clouds cleared about five o’ clock. There was no wind and the pitch was yielding, a relief for the players after the fiery surface of the previous matches. Celtic stormed into attack from the opening kick-off, and put Hibernian’s defence – sometimes considered the Achilles’ heel of the Edinburgh side – under immediate pressure. Fernie was racing past the veteran Jock Govan at will and creating havoc down the left with his runs; twice in the first ten minutes Younger was forced to dive bravely at his feet to save a goal. Mochan and Collins were equally direct, and threatened Hibs’ goal repeatedly.

Overworked, Hibernian had to concede corner after corner – and behind that goal the Celtic support was at its noisiest and most Encouraging.

A goal finally came in 28 minutes, at a time when Hibernian appeared to have weathered the storm. Stein cleared – a routine clearance but directed at Fernie; the winger, seeing defenders converging on him, flicked the ball into Mochan’s path. The latter raced out of the centre-circle, apparently intent on dribbling towards the penalty area. Throughout his career, however, Mochan was a believer in doing the unexpected. He decided to shoot with his right foot, supposedly the weaker one, from close to 30 yards. The ball swept high into the net at the keeper’s right-hand corner, as Younger threw himself vainly towards it. Neil Mochan in subsequent years was to score memorable goals for Celtic but he never hit a ball harder.

The Celtic support went wild with’ delight, and the tumult lasted for several minutes; after the din had started to lapse into mere bedlam, the cheers broke out again spontaneously in tribute to the shot. The goal, of course, has entered the Celtic mythology. So unexpected and so powerful was the shot that estimates of the distance vary considerably. Shortly after the final, the Hibs players were preparing for an international tournament in Brazil. Tommy Younger mentioned in training that he had managed to get a finger-tip to the ball. His team-mate, Mick Gallacher, a keen Celtic supporter and Eire internationalist, interrupted him: ‘If you had, you would have broken your f***** hand!’

Celtic’s efforts to break down the Hibs defence continued to the interval, but Younger and his hard-pressed defenders held out: ‘ … and the one-goal lead with which they [Celtic] crossed over did no justice to the threats and alarms they were responsible for in the vicinity of Younger’s charge … As usual Celtic got everything in effort and artistry from Evans, the most consistent and effective wing half in the game. Mochan has given the Parkhead attack an alert, penetrative quality, and the others have responded to his mascot inspiration.’ (Edinburgh Evening News: 21 May 1953)

One minute before the interval the Celtic supporters were chilled into momentary silence when Gordon Smith, taking a long pass from Combe, sped past Rollo to cross a perfect ball. Reilly headed strongly for goal from ten yards, but Bonnar dived to his right to save at the post. After 44 minutes this first indication of the potential danger in Hibs’ forwards was an unwelcome foretaste of the second half – a half considered one of the most enthralling in Celtic’s history, but perhaps the longest and most tense ever endured by its supporters.

Within seconds of the restart Hibernian were on the offensive. And when the Hibs of that era attacked it was an exhilarating sight, as Archie Buchanan and Bobby Combe threw caution to the wind, augmenting that magnificent forward line in attempts to break the Celtic defence.

Smith, Johnstone, Reilly, Turnbull and Ormond: a quintet that adorned the football scene in the post-war seasons, names that could be rhymed off by every schoolboy in the country.

Gordon Smith, nicknamed ‘the Gay Gordon’ in the relatively innocent 1950s, was a pleasure to watch on the right wing; graceful and deadly, a scorer with head and foot, and an exceptional crosser of the ball, he could change the pattern of any match with his buccaneering forays. His partner, Bobby Johnston, could react with lightning speed and was sharp within the six-yard box, able to distribute the ball so well that, after his transfer to Manchester City, one English fan described him memorably: ‘That Johnstone. He could pass the ball with his arse.’

At centre, Lawrie Reilly was the quintessential striker. He was the epitome of alertness, skilled with head and feet, and never gave defences a moment to relax. He had earned a new nickname – ‘Last-Minute Reilly’ – after his late goals against England at Wembley, and against Tottenham Hotspur at Ibrox.

Eddie Turnbull at inside left was considered the least naturally talented member of the line, but he more than made up for that with a prodigious work-rate. He challenged for every ball, helped out in defence, provided a steady supply for the other forwards, and was recognised as the dead-ball expert. Willie Ormond at outside left could be ignored only at peril; slightly built and with a deceptive swerve, he was goal-hungry. Quietly courageous, he came back hom two broken legs in his career.

Immensely gifted, individually talented but with complementary skills, the five combined with a deadly artistry; the football they provided delighted many in the grim, austere Britain of the early 1950s.

As the minutes crawled past, it seemed impossible that any side could have withstood the Hibernian onslaught, but that night Celtic’s defence included some outstanding performers and a goalkeeper, often maligned, who on the night of 20 May 1953 was positively inspired.

John Bonnar, considered too small to be a dominating keeper, produced in that second half arguably the best display ever given by a Celtic goalkeeper. The intelligent Smith, aware of Bonnar’s frequent problems with high crosses, sent over a stream of cunningly-flighted balls – only to see Bonnar clutch them cleanly, punch them away when being challenged, or scrape them to momentary safety with his fingertips.

The inside forwards, Reilly and Johnstone, usually so deadly from close range, had to shake their heads in disbelief as Bonnar saved their headers in spectacular style – in Reilly’s case, the keeper had to twist in mid-air to deflect the ball over the bar. Turnbull drove a fierce shot round the ‘wall’ but Bonnar dived to parry the shot, and went down at Turnbull’s feet to block the rebound. Time after time the Celtic supporters behind the goal roared approval of his heroics.

He was not alone in his resistance: Haughney and Rollo, not always the steadiest of full backs, defended tenaciously against Ormond and Smith; Stein, an inspiring and reassuring figure in the middle, refused to allow Reilly any room to manoeuvre; McPhail, although often in danger of being over-run, never broke under the pressure and continued to use the ball well – indeed, on the one occasion when Bonnar was beaten, McPhail headed a hook-shot from Johnstone off the line. And Bobby Evans played at his incomparable best. In a career studded with magnificent performances, he never played a better game.

Hibernian continued to attack in waves, and Celtic continued to hold out. With four minutes left another magnificent save by Bonnar foiled Hibernian once again: ‘His [Turnbull’s] lob was perfectly fIighted. Johnstone rose, and with a turn of the head, sent the ball speeding for goal. It carried the stamp of the equaliser until, in the last split-second, up shot Bonnar’s hand to divert the ball over the bar. Johnstone – unluckiest of all Hibernian forwards – could be excused for throwing up his arms in despair; and, as the players sorted themselves out for the flag kick, his disappointment did not prevent him from sportingly patting the goalkeeper on the back.’ (Edinburgh Evening News: 21 May 1953)

The corner kick was cleared by Evans as far as Fernie, back helping out in defence, who released Bobby Collins. The diminutive Celt raced up the wing, gaining seconds of relief for the defence, and beat Paterson neatly. He slipped the ball across to Walsh and the redhead shot past Younger. The ball was scrambled off the line by Howie but only as far as Walsh, who smashed it into the net.

Still, Hibs rallied yet again and Reilly’s shot was turned on to the base of the post by Bonnar: seconds later the whistle went and Bonnar was hugged by his team-mates. The Hibernian players joined in the congratulations, but must have been dismayed. Indeed, one of their team later described it as his ‘greatest disappointment in football’. Willie Ormond’s feelings were graphic: that Celtic team were ‘a puir bloody lot’ and he still bitterly regretted the fact that his side ‘couldna get one by that bugger Bonnar in 1953.’ (Interview with David Potter in The Celt, August 1994)

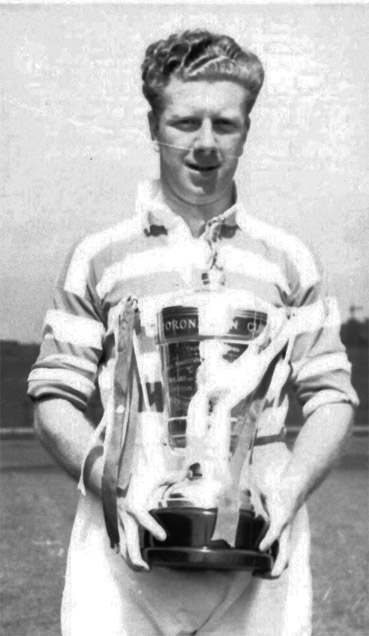

At the close of the match the Coronation Cup was presented to Stein by Lord McGowan, an honorary president of the SFA. The trophy, a solid silver cup standing 22 inches high surmounted by the representation of a footballer, and with a silver-gilt profile of the Queen on one side, was not paraded for the crowd to admire.

Both teams were ushered into the pavilion, each player clutching a solidsilver replica of the trophy. Despite the roars – that turned to slow handclapping of the crowd, most of whom stayed in their places for 15 minutes, the teams were ordered to remain inside .

Thousands waited outside the Hampden grandstand later, hoping to get a glimpse of the players and the trophy. Jimmy McGrory made a brief appearance at the doorway, but could not produce a sight of the Cup for the throng. Because the match had been carried on BBC Radio, the news had spread around Glasgow like bushfire and whole families gathered to celebrate in the streets of Celtic strongholds such as the Gorbals, and thousands cheered the Celtic bus making its way to a victory banquet in the city centre.

Throughout it all, seated on top of the bus surrounded by happy team-mates, Jock Stein clutched the trophy as if for dear life, with the dazed expression of one who has realised all his ambitions.

Reviewing the year, an English sports writer dubbed 1953 ‘the year of the veterans’, but he was not thinking of Jock Stein and the fairy-tale transformation in his career. Indeed it is highly unlikely that he had ever heard of the player, and he could never have imagined that one of the most significant chapters in British football was now under way.

The writer’s interest lay in two legendary sporting figures whose careers had culminated in spectacular fashion. At Wembley, hard-bitten reporters broke down in the press-box, while thousands on the terracings (or watching on television) wept with joy as Stanley Matthews sparked a late fightback by Blackpool and won – finally – the FA Cup-winner’s medal he had long cherished. The whole country celebrated with Matthews, at the age of 38 the most renowned football player in the world.

A month later at Epsom the ageing jockey, Gordon Richards, preparing to retire and recently knighted for his contribution to racing, won his first Derby at the 28th attempt; he took his mount, Pinza, to the front, two furlongs from home, and held off the Queen’s horse, Aureole, to win amid frenzied cheering

Between these two momentous sporting events, an unfashionable journeyman player, at the age of 30, seemed to have scaled his own personal Everest in the same year that the famous mountain had been conquered at last. He may have thought that football could have little more to offer him. If so, for once, he was totally wrong.