Happy May 25th!

“Sooner or later they’ll get the winner.”

Inter captain Picci to goalkeeper Sarti.

Inverting The Pyramid is Jonathan Wilson’s superlative book on the evolution of football tactics. Here’s an extract from his chapter on Catenaccio, in which the author offers an interesting pespective on that famous day in 1967 from the point of view of some of the Italian players on the receiving end of Jock Stein’s attacking tactics.

Above: Helenio Herrera, Inter coach in 1967. He pioneered the use of psychological motivating skills including slogans that were often plastered on billboards around the ground and chanted by players during training sessions. He also enforced a strict discipline code, for the first time forbidding players to drink or smoke and controlling their diet – once in Inter he suspended a player after telling the press “we came to play in Rome” instead of “we came to win in Rome”. He also sent club personnel to players’ homes during the week to perform ‘”bed-checks”. He introduced the ritiro, a pre-match remote country hotel retreat that started with the collection of players on Thursday to prepare for a Sunday game. Apart from that he was quite laid back.

It was in 1967 that Herrera’s Inter disintegrated, and yet the season had begun superbly, with a record breaking run of seven straight victories. By mid-April they were four points clear of Juventus at the top of Serie A, and in Europe had had their revenge on Real Madrid, beating them 3-0 on aggregate in the quarter-finals. And then something went horribly wrong. Two 1-1 draws against CSKA Sofia in the semi-final forced them to a playoff – handily held in Bologna after they promised the Bulgarians a three-quarter share of the gate receipts – and although they won that 1-0, it was as though all the insecurities, all the doubts, had rushed suddenly to the surface.

They drew against Lazio and Cagliari, and lost 1-0 to Juventus, reducing their lead at the top to two points. They drew against Napoli, but Juve were held at Mantova. They drew again, at home to Fiorentina, and this time Juve closed the gap, beating Lanerossi Vicenza. With two matches of their season remaining – the European Cup final against Celtic in Lisbon, and a league match away to Mantova – two wins would have completed another double, but the momentum was against them. If Inter were going to defend, the logic seemed to be, Celtic were going to attack with everything in their power.

And Inter were set on defending, particularly after Mazzola gave them a seventh-minute lead from the penalty spot. They had done it against Benfica in 1965, and they tried to do it again, but this was not the Inter of old. Doubts had come to gnaw at them, and as Celtic swarmed over them they intensified. ‘We just knew, even after fifteen minutes, that we were not going to keep them out,’ Burgnich said. ‘They were first to every ball; they just hammered us in every area of the pitch. It was a miracle that we were still 1-0 up at half-time. Sometimes in those situations with each minute that passes your confidence increases and you start to believe. Not on that day. Even in the dressing room at half-time we looked at each other and we knew that we were doomed.’

For Burgnich, the ritiro had become by then counter-productive, serving only to magnify the doubts and the negativity. ‘I think I saw my family three times during that last month,’ he said. ‘That’s why I used to joke that Giacinto Facchetti, my room-mate, and I were like a married couple. I certainly spent far more time with him than my wife. The pressure just kept building up; there was no escape, nowhere to turn. I think that certainly played a big part in our collapse, both in the league and in the final.’

On arriving in Portugal, Herrera had taken his side to a hotel on the sea-front, half an hour’s drive from Lisbon. As usual, Inter booked out the whole place. ‘There was nobody there, except for the players and the coaches, even the club officials stayed elsewhere,’ Burgnich said. ‘I’m not joking, from the minute our bus drove through the gates of the hotel to the moment we left for the stadium three days later we did not see a single human being apart from the coaches and the hotel staff. A normal person would have gone crazy in those circumstances. After many years we were somewhat used to it, but by that stage, even we had reached our breaking point. We felt the weight of the world on our shoulders and there was no outlet. None of us could sleep. I was lucky if I got three hours a night. All we did was obsess over the match and the Celtic players. Facchetti and I, late at night, would stay up and I isten to our skipper, Armando Picchi, vomiting from the tension in the next room. In fact, four guys threw up the morning of the game and another four in the dressing room before going out on lhe pitch. In that sense we had brought it upon ourselves.’

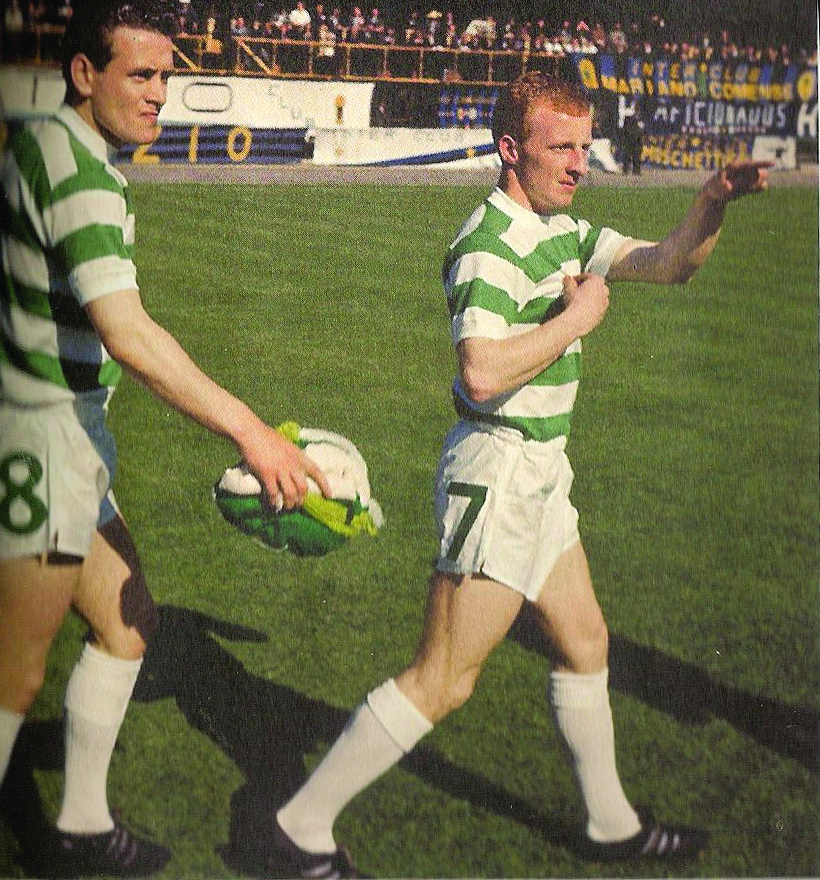

Jimmy Johnstone and Willie Wallace size up their oppoents while walking onto the Lisbon pitch. Jinky seems to have spotted someone he can swap jerseys with – a wildly optimistic idea for more reasons than one.

Celtic, by contrast, made great play of being relaxed, which only made Inter feel worse. In terms of mentality, it was catenaccio’s reductio ad absurdum, the point beyond which the negativity couldn’t go. They had created the monster, and it ended up turning on its maker. Celtic weren’t being stifled, and the chances kept coming. Bertie Auld hit the bar, the goalkeeper Giuliano Sarti saved brilliantly from Gemmell, and then, seventeen minutes into the second half, the equaliser arrived. It came thanks to the two full-backs who, as Stein had hoped, repeatedly outflanked Inter’s marking. Bobby Murdoch found Craig on the right, and he advanced before cutting a cross back for Gemmell to crash a rightfoot shot into the top corner. It was not, it turned out, possible to mark everybody, particularly not those arriving from deep positions.

The onslaught continued. ‘I remember, at one point, Picchi turned to the goalkeeper and said, “Giuliano, let it go, just let it go. It’s pointless, sooner or later they’ll get the winner,’’’ Burgnich said. ‘I never thought I would hear those words, I never imagined my captain would tell our keeper to throw in the towel. But that only shows how destroyed we were at that point. It’s as if we did not want to prolong the agony.’

Inter, exhausted, could do no more than launch long balls aimlessly forward, and they succumbed with five minutes remaining. Again a full-back was instrumental, Gemmell laying the ball on for Murdoch, whose shot was diverted past Sarti by Chalmers. Celtic became the first non-Latin side to lift the European Cup, and Inter were finished.

Worse followed at Mantova. As Juventus beat Lazio, Sarti allowed a shot from Di Giacomo – the former Inter forward – to slip under his body, and the scudetto was lost. ‘We just shut down mentally, physically and emotionally,’ said Burgnich. Herrera blamed his defenders. Guarneri was sold to Bologna and Picchi to Varese. ‘When things go right,’ the sweeper said, ‘it’s because of Herrera’s brilliant planning. When things go wrong, it’s always the players who are to blame.’

As more and more teams copied catenaccio, its weaknesses became increasingly apparent. The problem Rappan had discovered – that the midfield could be swamped – had not been solved. The tornante could alleviate that problem, but only by diminishing the attack. ‘Inter got away with it because they had Jair and Corso in wide positions and both were gifted,’ Maradei explained. ‘And, also, they had Suarez who could hit those long balls. But for most teams it became a serious problem. And so, what happened is that rather than converting full-backs into liberi, they turned inside-forwards into liberi. This allowed you, when you won possession, to push him up into midfield and effectively have an extra passer in the middle of the park. This was the evolution from catenaccio to what we call “il giocco all’ Italiano” – “the Italian game”.’

In 1967-68, morale and confidence shot, Inter finished only fifth, thirteen points behind the champions Milan, and Herrera left for Roma. Catenaccio didn’t die with la Grande Inter, but the myth of its invincibility did. Celtic had proved attacking football had a future, and it wasn’t just Shankly who was grateful for that.